Other nothern regions.

Sunday, October 13, 2024

Nothern lights.

Other nothern regions.

Saturday, October 12, 2024

Tuesday, October 8, 2024

advice

Bill Gates was invited by a high school to give a lecture. He arrived by helicopter, took the paper from the pocket where he had written eleven items. He read everything in less than 5 minutes, was applauded for more than 10 minutes non-stop, thanked him and left in his helicopter. What was written is very interesting, read:

MMD

May be a repeat.

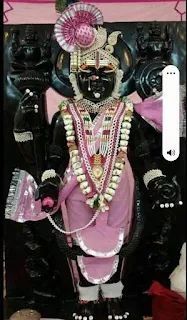

mAdhava mAmava dEva krSNa

Sunday, October 6, 2024

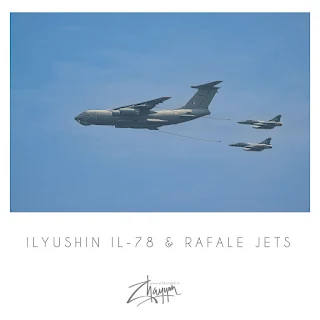

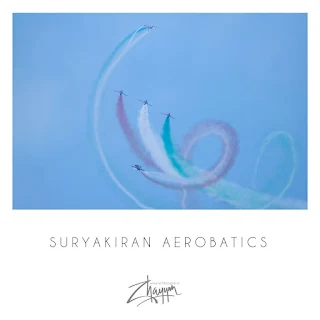

Air show.

Thursday, October 3, 2024

Kintsugi.

Kintsugi: The Art of Embracing Imperfections

Kintsugi, a traditional Japanese art form, translates to "golden joinery" or "golden repair." It involves mending broken pottery using lacquer mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum. The philosophy behind kintsugi goes beyond merely fixing an object; it celebrates its fractures and history, turning damage into something unique and beautiful. This practice, rooted in the Zen Buddhist philosophy of wabi-sabi, embraces imperfection, impermanence, and the acceptance of change as an inherent part of life.

Origins of Kintsugi

The art of kintsugi originated in the late 15th century during the Muromachi period in Japan. According to legend, the practice began when the Japanese shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa sent a damaged Chinese tea bowl back to China for repairs. Upon its return, the bowl was restored with unsightly metal staples, which motivated Japanese artisans to develop a more aesthetically pleasing method of repair. Thus, kintsugi was born. This new technique aligned with the cultural values of beauty, impermanence, and respect for the object's history.

The Philosophy of Kintsugi

At its core, kintsugi embodies the idea that brokenness is not something to hide but rather to honor. The mended cracks and fissures are highlighted with precious metals, creating a piece of art that tells a story of resilience and transformation. Kintsugi teaches that experiences of loss or damage do not diminish the value of a person or object. Instead, they add to its beauty and uniqueness.

This practice reflects the broader Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi, which finds beauty in the imperfect, the transient, and the incomplete. Unlike Western ideals of perfection, which often prioritize flawless symmetry and permanence, wabi-sabi accepts the natural cycle of growth and decay. The imperfections of the repaired pottery, now made more striking by the golden veins, become metaphors for life’s inevitable imperfections.

Kintsugi in Contemporary Culture

Today, kintsugi has transcended its original craft and has been adopted as a powerful metaphor for personal growth and healing. Many people find comfort in the idea that their own emotional scars and life challenges can be seen as something to embrace rather than hide. The concept of “being made more beautiful for having been broken” resonates with individuals experiencing loss, failure, or trauma. Kintsugi invites reflection on how we handle adversity and offers an empowering perspective on the value of imperfections.

Additionally, in an age of mass production and consumerism, kintsugi encourages mindful consumption by emphasizing the value of repair over replacement. Rather than discarding broken objects, kintsugi suggests that with care and craftsmanship, damaged items can gain new life. This approach aligns with modern sustainability movements that challenge the throwaway culture by encouraging people to value the stories and longevity of their possessions.

Conclusion

Kintsugi is more than just a method of repairing pottery; it is a philosophy that teaches us to find beauty in brokenness, to honor the passage of time, and to embrace imperfection. By highlighting the fractures rather than concealing them, kintsugi elevates the damaged object into something richer and more meaningful. This ancient Japanese art form offers a timeless lesson: that our struggles, far from diminishing us, have the potential to make us stronger, wiser, and more beautiful.

Monday, September 30, 2024

The divine eagle.

Garuda is a significant figure in Hindu mythology, known as a powerful and divine bird who serves as the mount (vahana) of Lord Vishnu, one of the principal deities of the Hindu pantheon. Garuda is much more than just a vehicle for Vishnu; he represents strength, courage, and swiftness, and embodies the transcendental powers needed to bridge the material and divine worlds.

This essay explores the origins, characteristics, symbolism, and cultural importance of Garuda in Hindu mythology, while also tracing his presence across other cultures such as Buddhism and Jainism.

1. Origins and Mythological Background

Garuda's story is rooted in ancient texts, including the Mahabharata, Ramayana, and various Puranas. He is the son of the sage Kashyapa and Vinata, one of the thirteen daughters of Prajapati Daksha. Garuda’s birth was a result of a long-standing rivalry between his mother Vinata and her co-wife Kadru, the mother of serpents. This rivalry, a fundamental theme in his story, mirrors the eternal struggle between birds and snakes in nature.

The myth begins with a bet between the two wives. Kadru tricks Vinata into becoming her slave. To free his mother, Garuda is asked to bring Amrita, the nectar of immortality, from the gods. In doing so, Garuda displays extraordinary power and cunning, defeating formidable obstacles and opponents. However, once he retrieves the Amrita, he does not consume it himself, but rather returns it to the gods. As a reward for his integrity and valor, Vishnu makes Garuda his vahana, and grants him immortality.

2. Garuda’s Iconography and Symbolism

Garuda is often depicted as a giant eagle or eagle-like being, with the body of a man and the wings and beak of a bird. His wings are typically described as golden, his body radiant, and his presence commanding. His speed is said to be unmatched, and he is often portrayed soaring through the skies, with Vishnu mounted on his back, carrying weapons such as a mace or discus (chakra).

The iconography of Garuda is not just an artistic depiction but carries deep symbolism. His association with the sky and flight represents liberation from earthly bonds, spiritual freedom, and the transcendence of human limitations. In many depictions, Garuda is shown subduing snakes or Nagas, symbolizing his role as a protector of righteousness, fighting against evil, deception, and poison (both literal and metaphorical).

Garuda’s association with snakes also symbolizes the eternal conflict between light and darkness, truth and falsehood, good and evil. In some interpretations, the serpent represents ignorance, which Garuda, as a force of divine knowledge, seeks to conquer.

3. Garuda in Hinduism

Garuda holds a unique position in Hindu worship, particularly in Vaishnavism, where devotees of Vishnu often revere Garuda as well. Statues and depictions of Garuda are commonly found in temples dedicated to Vishnu, often placed near the entrance or at the foot of the deity’s image. The Garuda Purana, one of the eighteen Mahapuranas, is attributed to Garuda as the narrator, and deals with various religious and philosophical teachings, including rituals, ethics, and cosmology.

In daily practice, Garuda is invoked in prayers for protection, speed, and strength. His courage in fighting the serpents makes him a symbol of fearlessness, while his devotion to Vishnu represents the ideal of selfless service to the divine. Some temples even dedicate special prayers or offerings to Garuda as part of regular rituals to ensure protection from evil forces and health hazards such as snakebites.

4. Garuda Across Cultures

While Garuda’s origins are in Hindu mythology, his influence transcends the borders of India. In Southeast Asian cultures, especially in Indonesia, Thailand, and Cambodia, Garuda has become a national and cultural symbol. For instance, in Indonesia, Garuda is the national emblem, where it symbolizes strength, vigilance, and the pursuit of sovereignty and freedom. The national airline of Indonesia is even named Garuda Indonesia.

In Buddhist mythology, Garuda also appears as a protector and a figure of immense power, though his role is somewhat reinterpreted. In some texts, Garuda is seen as a guardian of the Buddha and the Dharma, representing the ability to rise above ignorance and attachment. Similarly, in Jainism, Garuda is mentioned in various texts, although he does not play as central a role as in Hinduism.

5. Garuda in the Mahabharata and Other Texts

In the Mahabharata, Garuda is a significant figure, with his story interwoven with the central narrative. His presence emphasizes the importance of loyalty, self-sacrifice, and devotion. As the king of birds, Garuda is also a metaphor for kingship and authority, and his relationship with Vishnu symbolizes the bond between the ruler and the divine.

Garuda is also central to various later Puranic tales, such as the Vishnu Purana and the Bhagavata Purana. These texts highlight his role as a protector of Dharma (righteousness) and as a divine intermediary, capable of moving between worlds. The Garuda Purana, as mentioned earlier, is an important text in this context, providing a comprehensive understanding of life, death, and the afterlife.

6. Garuda in Art and Architecture

Garuda’s prominence is also visible in the art and architecture of Hindu temples. His image is often carved on the pillars and entrances of temples dedicated to Vishnu. In Southeast Asia, particularly in ancient Khmer and Thai architecture, Garuda is a recurring motif, symbolizing protection and power. For example, in Angkor Wat, the grand temple complex in Cambodia, Garuda is seen as part of the architectural design, guarding the temple gates and corridors.

In Indian temple architecture, Garuda is sometimes depicted in a kneeling position with folded hands, expressing his devotion to Vishnu. These representations serve as a reminder of the ideals of service, humility, and loyalty, which Garuda embodies in his relationship with Vishnu.

7. Garuda in Contemporary Culture

Garuda’s mythological and symbolic significance continues to influence contemporary culture. In modern India, Garuda remains a popular figure in religious iconography and art, while also being adopted in various forms of media such as comics, films, and television series. In Indonesia, Garuda remains a potent symbol of nationalism, appearing on currency, government seals, and in official ceremonies.

The mythical bird also appears in modern literature and storytelling, where he is often reinterpreted in the context of modern values, such as environmental conservation, reflecting the need to protect nature and wildlife.

8. Conclusion

Garuda is not just a mythological figure; he embodies profound philosophical concepts within Hinduism and beyond. As a symbol of freedom, strength, and divine power, Garuda represents the aspirational qualities of spiritual liberation and moral integrity. His presence in various cultural contexts, including Southeast Asian nations, highlights his enduring influence across time and geography.

Garuda’s role as Vishnu’s mount and his fight against the Nagas are metaphors for the eternal struggle between good and evil, knowledge and ignorance. His image, with its awe-inspiring wings and fierce beak, serves as a powerful reminder of the divine potential within every individual to rise above challenges and achieve greatness.

Garuda’s legacy, both in religious and secular contexts, continues to inspire, representing the soaring spirit of human ambition and the quest for transcendence.