Thursday, May 28, 2020

Wednesday, May 27, 2020

Tuesday, May 26, 2020

Furloughed.

You’ve Been Furloughed. Now What?

Nicholas Eveleigh/Getty

Images

Nicholas Eveleigh/Getty

Images

Many of us join companies

thinking we will have a clear path of progression and growth for years to come.

For the most part, since the last recession, this has been true. But what

started as a health crisis has evolved into a redefinition of work, with an estimated 18 million Americans furloughed since mid-March.

The economy has taken a

serious plunge, and now the millions waiting for their careers to resume

are faced with a new question: Should I wait for my furlough to end or should I

apply for other jobs?

FURTHER READING

Furloughs —

a word that until recently was unfamiliar to most people, including business

leaders — are the talk in boardrooms and at breakfast tables around the world.

Furloughs are temporary, unpaid leaves of absence that several businesses have

bestowed on employees due to financial hardships. The catch is that employees

on furlough are able to maintain their health insurance and 401K benefits. At

the same time, they are not provided a salary during the leave, and under such

circumstances, can collect unemployment and benefit from the CARES Act.

A key consideration in

furloughs is that the employees have the opportunity to be called back to their

jobs once their organization recovers — though there is no guarantee that this

will happen. In part, whether or not they return will be contingent on the

demand for their former jobs to return. Many people in this position are

struggling to gauge which decision is wiser: waiting for things to revert to

normal (or at least the new not-normal), or thinking in shorter term and

applying for a new job now.

In our view, there are

five key points to consider if you are debating whether to seek work during

furlough or not:

1. Can

you afford to wait?

This is purely a

financial question. With enhanced unemployment benefits, furloughed Americans

can earn on average $24 an hour for four months. However, for many, this is

insufficient to support their lives, and the limited timeframe is concerning.

Furloughs can last for up to six months before a company is required to decide

if a worker is returning or not. This means there is a chance of economic

exposure pending how long the furlough lasts. There is also the risk that

workers will not be called back to work post-crisis and the opportunities that

were available mid-crisis will be missed.

For those who can’t afford

to wait, there are some good options. You can apply for new roles both

permanent or temporary to keep learning and earning. Although we have a record

number of people filing unemployment, according to ManpowerGroup’s real time

view of all open jobs in the U.S., we had 5.8 million open as of May 7. Even if

you don’t want to commit to a new career path, you can take on temporary work

that allows you to try out a career change before committing to it.

2. Do

you want to wait?

Furlough is a loaded

word, but it doesn’t have to be defined by fear. It can be the beginning of a

new future. Many of us get caught in the trap of normalcy and routine in our

careers and forget to re-examine our interests and life objectives. This crisis

gives us time to re-evaluate our futures in a way that we may have never been

given before. We are forced to stop and think: Is this truly my desired path?

Is this a job I love and want to do again? Or is it time to think of doing

something new?

Take some time to pause

and think. Reimagine your potential in a way that the former normalcy of life

wouldn’t have allowed. Ask yourself if your job is worth waiting for. Do you

want to return to your pre-crisis life? If there is any inkling of doubt in

your mind, there is no downside to applying for something new, and seeing what

could materialize as a different future.

3. Will

what you gain be better than what you leave behind?

The familiar concept of

the “grass is greener” is often true when we think about career options. Analyzing the

pros and cons of your job considerations can play a vital role in making an

informed choice. Take a fresh look at what you enjoy in your furloughed role

and the benefits it provides — from essentials like pay and health care to the

more personal like your hard-earned reputation. All of these elements carry

value. Now compare them to what you could be gaining in a new role at a new

organization. Consider your desired flexibility, learning opportunities, and

perhaps most importantly, the future demand of the work you could pursue

compared to the work you are waiting to return to.

While comparing, remember

that there will always be trade-offs (e.g., less money for more fun, more money

for less freedom, and more prestige for less meaning). Ensure that these are

worth the pursuit and aligned with your core values.

Before making a decision,

this is also the perfect time to discuss your career with your current employer

and see if there are ways to reshape it in ways that work for both of you. It

is possible your workplace may be supportive of you applying for other business

opportunities or work with you on an adjusted scheduled. Ask about the things

you’ve wanted but were too afraid to ask for before. If you decide to pursue a

change after these considerations, you will be doing it with the most available

information.

4. Are

you ready to build a remote network?

Let’s say you are

committed to the exploration and ready to take on a sprint or two for your

future. It’s important to understand how joining a new company during this

crisis and post-crisis will likely play out. Nobody knows, but you can and must

make bets. Without speculation, there is no planning, and planning is all you

can really do right now.

Undoubtedly, there will

not be large onboarding classes where you get the chance to network with

leadership and build a cohort of other new hires. But you can still ask as many

questions as needed during the interview process to ensure that your bets are

as data-driven as possible. Perhaps there won’t be hands-on training, even if

your new role is labor intensive, which is likely, since for most jobs the

largest proportion of learning is on-the-job, practical learning. This does not

mean that companies will stop doing formal training. However, you will need to

be a student and extract formal learnings from every experience.

Given this, you should

consider how you learn best. Can you learn in a virtual environment? How much

supervision do you want and need? Do you prefer to follow instructions or find

your own way? To be successful in this environment, you will likely need to

step outside of your social comfort zone as well. Can you build a network

without physically seeing your co-workers? Do you know how to display key

social skills like empathy and learn a new etiquette online? Think about these

questions as you explore options.

Remember, humans are

extremely adaptable. But we are also quite lazy — always looking for more

efficient and effortless ways to solve our immediate problems. We learn only

when we have to, and now, the whole of humanity must figure out what to do

under these circumstances. The world will be changed even as we reopen it.

Understanding how those changes impact your orientation into a new job and

company is vital.

5.

Would upskilling for the long term be more valuable than new work for right

now?

Finally, there is another

option — let’s call it “working the wait.” The wait for work doesn’t have to be

wasted. It can also be a self-investment. There are numerous options for free

learning and upskilling right now — from Yale University offering one of its

most popular courses on the science of happiness to ManpowerGroup offering free courses in

partnership with the University of Phoenix, as well as a range of

open-source content curators that can help you identify your key learning needs.

The opportunities to learn while you are waiting to earn are numerous.

Even pre-crisis, we knew

that skills were changing with the pace of technology. In many ways the crisis

has accelerated that technology and the possibilities of making a virtual

contribution. Now is a great time to know what skills will be in demand later

on — both soft and hard skills — and invest in future-proofing yourself for the

role you are waiting to return to or the role you choose to pursue during

furlough.

Think of this employment

“time out” as a chance to redefine your short and long-term thinking on career

marathons and job sprints. Use it to reimagine your future because, even when

we return to work, it will be very different than it was in the past.

Prastana traya

variola

- SAYANTANI NATH

- DECEMBER 9, 2019

- HEALTH CARE HISTORY

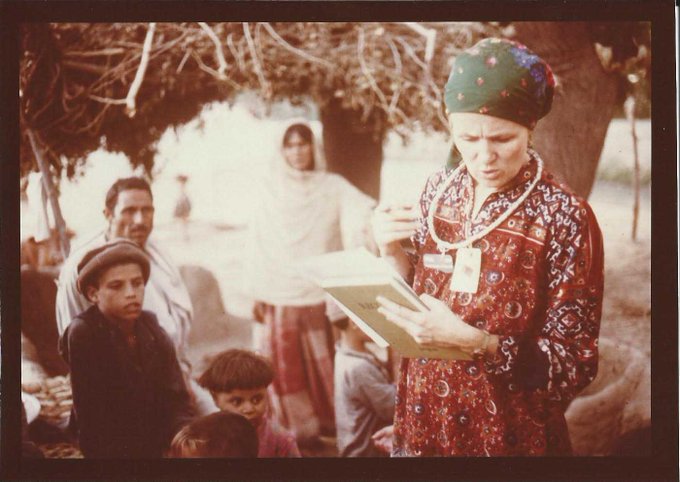

Mary Guinan

Dr. Mary Guinan: The Epidemiologist Who Gave CNN Sass For Asking A Stupid Question http://ow.ly/4mO8uK @npratc

Cornelia E Davis